by Charles Bramesco

Mon 28 Feb 2022 13.56 EST

The time has come for a long overdue conversation about a menace with the potential for a sweeping crisis, an urgent threat to the very fabric of American society: poop. Everybody does it, but we’d rather not think about it, and avoid discussing it unless we have to. In new docuseries Wasteland (now streaming on Paramount Plus), director Elisa Gambino informs us in no uncertain terms that we do have to, and isn’t hesitant about showing us why.

“The philosophy for us was to try to present poop in a serious way, which is hard, because it’s so easy to slip into potty humor,” Gambino said over the phone during a stopover in Montana. “But we wanted to look at poop and how it affects environmental justice, to treat it with seriousness without being so serious that people can’t watch it. You try to find a middle ground.”

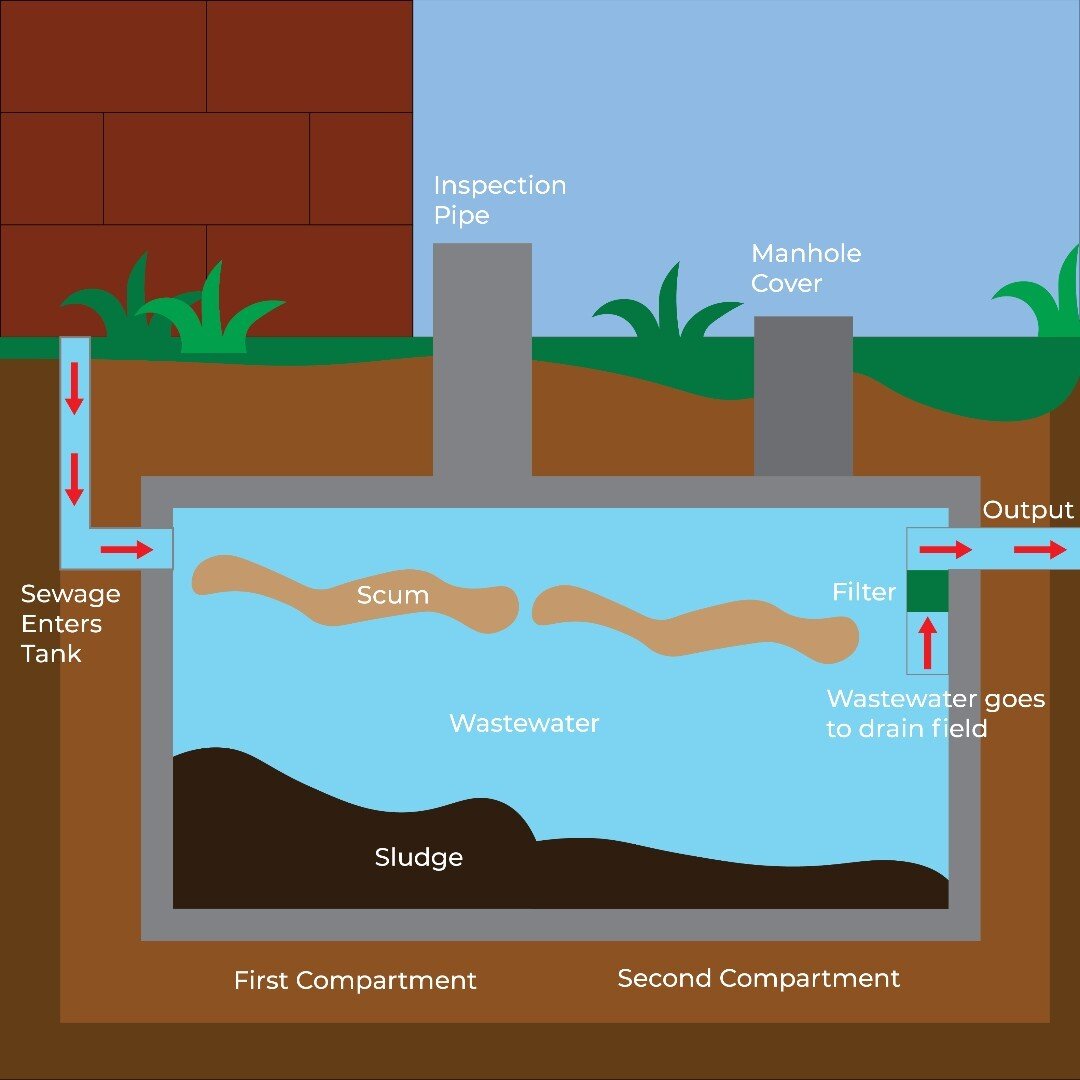

Fecal matter represents a clear and present danger to that most precious human right of access to clean water, contaminating natural sources like streams and bubbling up into bathtubs and sinks due to faulty septic infrastructures. In choosing to shed fresh light on this vital, oft-ignored topic, Gambino faced an unsavory predicament. How much depiction is too much? Can something be too gross for TV? (There were times when she wasn’t sure she’d make it, developing headaches from the potent stenches along with her husband and director of photography Neal Broffman.) She didn’t want to shortchange just how abject some of this spillage and seepage could be, but at the same time, she understood that viewers have their limits. Like the rickety, untended pipes leaking bacteria into the water supply, people can only take so much shit before hitting a breaking point.

“The episodes are quite beautiful,” she says. “They’re cinematic. We tried to create a feeling of all-is-well, where on the surface, flowers are blooming and corn is growing. But then there’s a theme of the underlying. Some people have said this looks too good to be about poop … The whole year I spent working on this, I divided my friends into two groups: the ones that would let me talk to them about the series and politely listen, and the ones who would just look at me and then change the subject, or walk away. I was happy on Thursday, when it premiered and I could say, ‘Look! I was really doing something! I wasn’t just talking about poop!’ Now, I don’t have to talk about poop so much. But I can’t flush the toilet or turn on the faucet without thinking about it.”

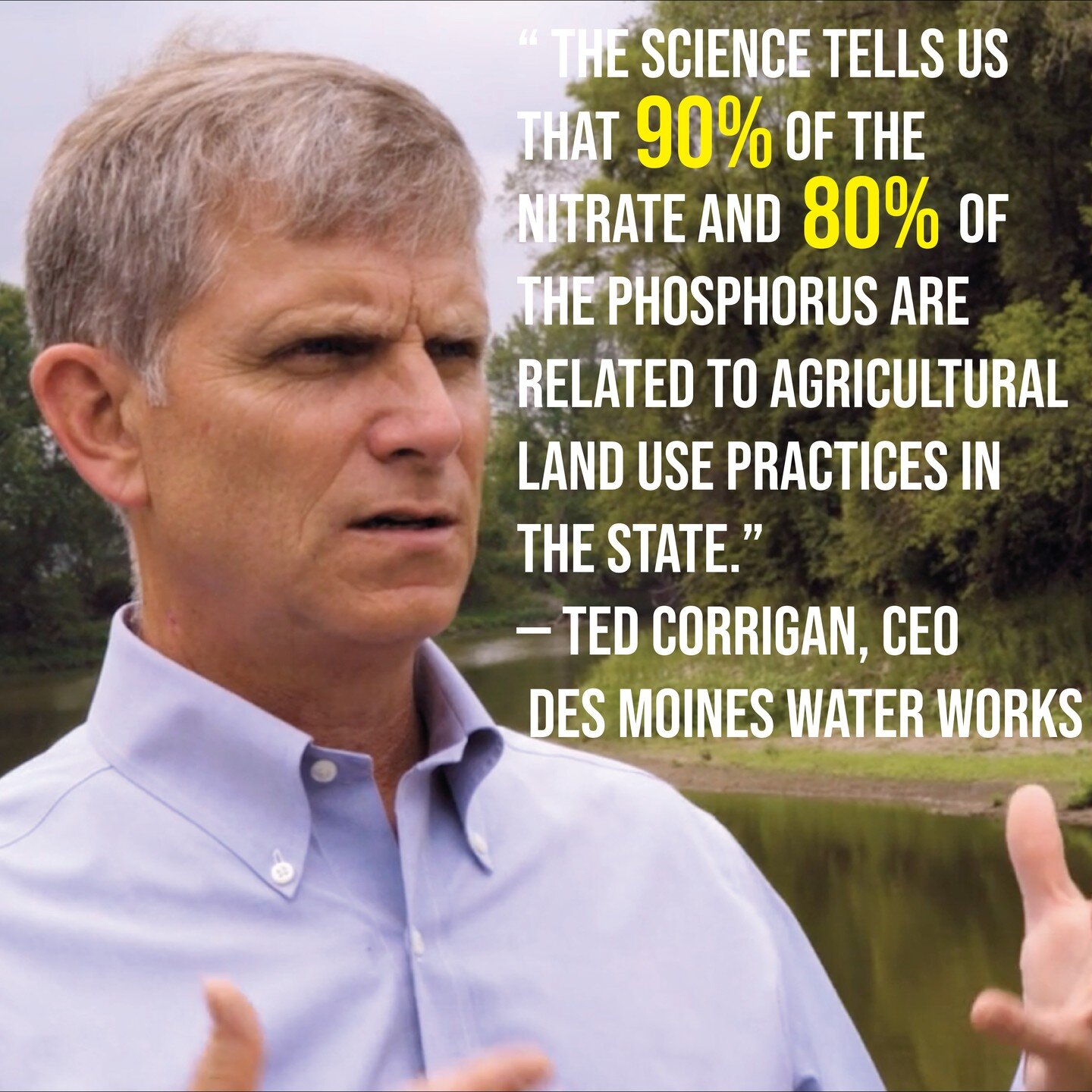

For the resilient souls featured in Gambino’s series, excrement isn’t something to think about, but a terrible fact of daily life. Each of the four episodes concentrates on the hazards of contamination in a different state, as onscreen reporter and executive producer Adam Yamaguchi interviews the public works officials, activists and ordinary folks caught up in the vast impact of this ecological quagmire. In Alabama, Lowndes county falls within the predominantly African American Black Belt,and the specters of centuries-old racism still wreak secondhand havoc on the underserved population. Just outside New York City’s limits, the people of Mount Vernon share horror stories of brown geysers pumping their homes full of raw sewage. Down in southwest Florida, septic tanks have caused lethal “algal blooms” that wipe out fish and other regional fauna while rendering water unsafe to drink. And in Iowa, the booming pig-farming industry generates more manure than anyone knows what to do with, and locals pay the price in cancer.

Across each case, the constant is the insidious way that institutional neglect ripples out to create personal consequences. “I think sometimes too much responsibility is put on individuals, and we don’t think enough about the cause,” Gambino says. “In Alabama, people are responsible for their own septic system and they get absolutely no help. We’re always telling people to recycle their plastic at the cost of thinking about who’s making the plastic. People think it’s an individual choice to live in a house with a septic tank, but it’s not. This is everybody’s problem. We need to look at the legislation in Iowa that’s not serving the people. Infrastructure money needs to go to Mount Vernon and released to the people once received. It’s not just the collapsing pipes, it’s people doing things to make this job so much harder.”

Without funding or the staff it would pay for, Mount Vernon Public Works Commissioner Damani Bush has no choice but to rush around town, plugging up each successive calamity like he’s jamming corks into one big sinking ship. Over and over, we’re shown how natural and human-made factors combine to leave our most vulnerable in jeopardy. One might sense a feeling of futility creeping on as they watch, as if the Earth has begun rejecting us and we’re powerless to stop it, but the truth is that there’s still plenty to be done. In Alabama, laws long since out-of-date hold the towns of Lowndes county down as much as any inevitabilities from the changing climate. The state has largely left the low-income community of mostly Black residents to fend for themselves in the fight for even the most basic creature comforts of modern life.

“In the episode about Alabama, Dr Robinson talks about how following the civil rights movement, there was a lot of hope for people across the Black Belt that they’d find new prosperity,” Gambino says. “Every tool was used to make sure this didn’t happen. These systems that they rely on, the expensive systems of engineering – they’re left on their own to maintain them after they’ve been purchased. There isn’t even insurance available, where you can pay monthly and then be all right if your septic tank breaks. We have it for cars and homes, and this is sanitation, no less important. In Mount Vernon, people might look at an all-Black leadership and think that it can’t be an issue of racism, because look at local government. But the problems are so baked-in that they existed long before this change, divided by old racisms. I just want people to walk away with something to think about.”

While Gambino has accepted that the oncoming deluge of sewage represents a problem too vast for any of us to take on, her film nonetheless leaves us with a call to action. All we can do is hold lawmakers’ feet to the flames in our demands to adjust the laws, as in Iowa, where something as simple as a stricter ordinance against spraying manure on frozen ground could make a planet of difference. “Legislators have concrete knowledge of what needs to be done to address these problems,” Gambino says, “but there’s no will among the legislators to do anything.”

The structuring absence would seem to be the emergency conditions in Flint, Michigan, the most high-profile battleground in the fight for clean, non-contaminated water. But Gambino has observed a simplifying effect in how the public processes information that often places Flint at the forefront of this dialogue, as if we prefer to mentally constrain the sewage to a single location. The unfortunate truth, however, is that it’s everywhere. America is drowning in a vast sea of it, and we can’t afford to deny it any longer. If this feels like a stomach-turning thing to think about, just consider how much more visceral the response will be once it’s happening in your own home.

“Not to take anything away from Flint, that’s so important right now, but the focus on it has sometimes kept us from looking at other places as well,” she says. “There are millions of people across the United States with non-potable water. It’s like Commissioner Bush says – this is a nationwide problem. We didn’t even get into the situations with the Navajo Nation, for instance, or West Virginia. It’s happening everywhere.”